Recently, Direct HR published its annual survey about foreigners in China. In this article we highlight the main findings of this report.

The presence of foreign talent in China has historically played a pivotal role in bridging international expertise with domestic business needs, contributing significantly to sectors ranging from high-tech industries to manufacturing. Currently, a substantial shift in the dynamics of foreign employment in China can be observed.

More foreigners from developing countries

In 2024, the foreign workforce in China is significantly different from that of previous decades. There has been a decline in foreign nationals from developed Western and Asian countries, particularly in first- and second-tier Chinese cities, which have traditionally attracted most foreign nationals. In 2010, about half of the foreign population in China came from developed countries, such as United States, Germany and France (17% jointly) and South Korea, Japan and Singapore (33.5% jointly). Ten years later, in 2020, this percentage decreased to only 21.3% (8.9% and 12.4% respectively). Conversely, there has been a substantial rise in workers from developing Asian countries. 52% of the foreign nationals in China came from developing Asian nations Myanmar, Vietnam, and Laos, up from only 13% in 2010.

The number of Belgian nationals in China is also historically low. According to official data from China’s National Population Census, there were approximately 1578 Belgian residency permit holders in China in 2010. By 2020, that number had decreased to 1076. No official figures are available yet for 2023 or 2024. It is important to note that these numbers include more than just working expatriates. They also account for accompanying family members, students (with a stay longer than six months), and “returnees”—individuals originally born in China who now hold Belgian citizenship. As such, the actual size of the foreign workforce from Belgium may likely even be smaller.

This development reflects both the increased cost- consciousness among hiring companies, as well as a reassessment of China’s foreign worker needs. In recent years, China has focused on becoming more self-reliant in high-skill sectors. At the same time, it has addressed labor shortages in manufacturing by relying on low-skilled immigrants from neighboring countries to fill essential blue-collar roles.

Shift in geographical distribution within China

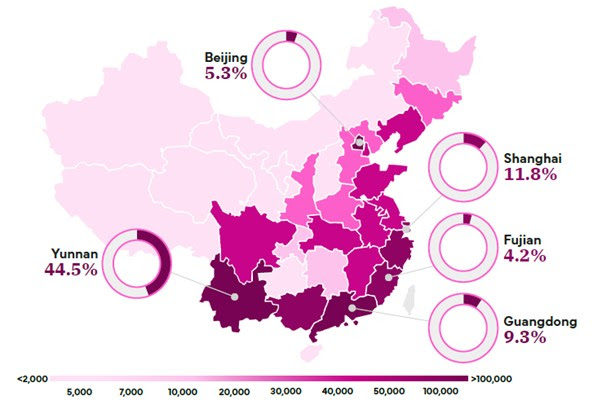

Another major difference is the destination of these foreign nationals in China. In the past, foreign nationals generally lived in major cities such as Shanghai, Beijing, and Guangzhou. By 2024, due to changing geopolitical dynamics, shifting economic demands, pandemic recovery and policy reforms, these big cities experienced declines of over 40% in their foreign populations.

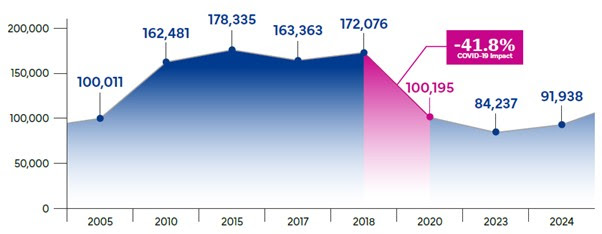

In Shanghai, the number of foreign nationals reached its peak in 2015, with approximately 178,335 residents. However, soon after, a sharp decline of -41.8% could be noticed between 2018 and 2020, as the foreign resident population dropped from 172,076 to 100,195. This substantial reduction can be attributed to the impact of COVID-19, which led to many foreign countries evacuating their citizens, many large multinational companies offering chartered flights to evacuate their foreign staff and families back home, and foreign students leaving China as their schools and universities were closed. After reaching a low of 84,237 in 2023, the foreign population showed a slight recovery in 2024, increasing to 91,938.

As of 2020, 75% of all foreign nationals are concentrated in five provinces: Yunnan, Shanghai, Guangdong, Beijing, and Fujian. Yunnan holds the largest share, with 376,689 foreign nationals, benefiting from its vicinity to Myanmar, Vietnam, and Laos, and the influx of factory workers and, to a lesser extent, the cross-border marriages these countries provide.

Shift in foreign workers’ profile

There has been a noticeable change in the types of foreign workers that China attracts, with an increase in lower-skilled workers from developing countries and a decrease in high-skilled professionals from developed nations. The demand for foreign employees from developed countries with a higher educational degree is at a low point amidst the current localization drive of Western companies in China.

The era of open-ended, lifestyle-driven expatriate careers in China is ending. In the past, a large portion of expatriates moved to China for the long term with their entire family, living in a luxurious apartment, having their own driver and sending their children to expensive international schools. Furthermore, compensation packages for foreign executives in China have decreased by around 25% from 2014 to 2024, with reductions in allowances for housing, school fees and flight reimbursements. And finally, the expatriate experience is no longer as seamless or attractive as it once was. Concerns over regulatory unpredictability, increasing nationalistic sentiment, and COVID-era border restrictions have left lasting impressions.

Recent years have witnessed more short-term specialists, staying in China no longer than 1-3 years, or project-based hires (expatriates hired for specific projects only). This new generation of foreigners is usually a bit younger, between 30 – 45 years old. Knowledge of Mandarin is evolving from ‘nice to have’ to ‘preferred’ or even ‘strongly preferred’. They are more dynamic and more entrepreneurial, with a growth-oriented mindset and an understanding of the Chinese digital media landscape.

Companies are also re-evaluating the necessity and role of expatriate assignments. Since mid-2023, a strong shift has been observed from foreign management to local management. This trend continues to persist and can be seen in both small and medium enterprises (SMEs) and multinational companies.

Despite all of the above, China still offers unique professional and personal growth opportunities for adaptable, high-skilled foreigners. For those who remain or arrive, the opportunities can be substantial, especially in sectors like high-tech, education, and corporate leadership.

Please contact the Belgian-Chinese Chamber of Commerce (BCECC) in case you have any questions.